High School Lockdown

How did it feel when they told you a shooter might be in the building?

There was a lockdown at one of my high schools last year, election day. “Swatting,” I guess it’s called, when someone prank calls a high school and says they’re going to come shoot the place up. Still boggles my mind that this is now a reality for kids, that we cannot say to them, “We can absolutely guarantee it won’t happen here.”

Every day is a gamble, and at some level, they know this. Just the other day, I asked a middle school student how she felt about the new no-phones policy. “I hate it,” she said. “What if someone comes, shoots the place up, and I can’t call my dad?”

Two days after the swatting last year, my colleague and I return to that high school for our weekly restorative circle during afternoon study hall. We show up once a week, every week, to sit in circle with whoever wants to drop in and risk sharing about their lives, their hearts, their truth. Or maybe just their favorite color. Their favorite food. Anything they offer, anything at all, is welcome, is sacred. Even if it’s bullshit. You keep treating them with reverence, the bullshit turns to gold eventually.

Before the period starts, this first circle after the lockdown, the students rush and swirl in the hallway like the currents of a powerful river and I start asking a few of them in passing what it was like, the lockdown. They shrug, shake off my question.

No big deal. Whatever. Just another day.

I don’t mistake this for the truth. Their armor against the truth has to be so thick. They can’t go there, can’t let themselves feel how it actually felt. How could they? If they actually felt it, would they be able to show up to school the next day? Could they continue on with business as usual, if they really squared themselves to the fact that business as usual now apparently includes the possibility of being maimed or murdered in the middle of math class?

Before the circle, my colleague and I decide we’ll try to invite them out anyway, see what happens if we ask them directly:

Tell us about the lockdown. What was it like for you?

That will be our prompt, we agree. Or in other words:

What did it feel like to be huddled in the corner with your entire class, away from the windows, keeping quiet, wondering if this was for real?

And then how was it when the police came in with their big guns to clear the room?

And when the authorities, whoever they are, said it was all just a hoax, what was it like to step out into the hallway again?

Our weekly circle is about two months old now, not a newborn wobbly-legged foal anymore, but far from full-grown. Today, we’ll see if we’re ready for a gallop.

It’s a big group again, somehow. I’m always a little surprised anyone comes.

We do the Welcome. We do the Grounding. Now we get into the Sharing Round and I lay out the prompt: What was the lockdown like for you? Tell us about your experience.

“Who wants to start us off?” I say.

A young man raises his hand, a sophomore. I send it to him and brace for impact. Because this kid is powerful. Some of the time he uses that power responsibly. Honestly. Speaks truth. Most of the time, though, our man plays around with it. He talks while others are doing the hard work of attempting to share. He gets other kids to laugh and snicker and hiss. Sends his insecurities ricocheting around the circle. You could call it “bullshitting.” You could call it “defiance” or “sabotage.” And maybe it is, at one level. At another level, though, I think he’s just testing out the space. Seeing what it is. How it will respond to him. Whether it will accept him as he is or force him to be different, manhandle him into compliance or invite him into the version of himself that comes out when he’s at home with his mom, or his grandmother, or whoever it is he truly trusts and respects and adores. He keeps coming back, every week. When he makes a show of walking out mid-circle, I tell him we need him. His power. Because goddamn does he know how to drop the mic when he decides to be real.

Like last week, when we were doing the Closing Round to finish out the circle—What’s something you’re grateful for?—and it got to him and all he said was, “Being Black,” and it hung there for a second or two in perfect beauty, and perfect power, and then an Arab kid, a freshman, goes, “Yeah, me, too,” and snorts, and our man goes, “You’re not Black,” and seeing things start to fall apart I come in with, “Thank you, ____, your gratitude is so powerful,” and then I send it to the Arab kid, “What’s your gratitude, ____?” and he goes, “Money,” to which I say, “Fair enough,” and round the circle we go, and round we will keep going until we all know that we are loved here, and cherished, and therefore safe to be real.

He said it himself at the beginning of the circle today. I asked him to come up with a question for us, for the opening round, the Grounding Round.

“What’s something you love?” he said.

“Beautiful,” I said, pleasantly surprised. “I love that question.” I took the mic, started to share something I love to start us off, when he said, “Hold on.”

“What’s up? You got something?”

“What’s something you love, and cherish,” he says.

“Perfect,” I said. “That is a perfect Grounding question.”

So we went around, warming up this post-lockdown circle, grounding, each of us risking a few words about what we love and cherish. When it was his turn to share on his own question, he mumbled something I didn’t understand about “honey” and a bunch of boys laughed, and he smirked, “It’s an inside joke.”

I chose not to pursue it. Moving on.

And so it was that we finally got to the Sharing Round—What was the lockdown like for you?—and this same sophomore boy, our man, raises his hand to start us off. He has the mic. I am bracing for impact.

“Scared,” he says. “Hiding. Running away.”

And then:

“Confused,” the young woman next to him says.

“Confused,” says the girl next to her.

Now it’s the teacher’s turn, our fellow circle-keeper. He tells us how intense it was for him to realize that he wasn’t just responsible for his own safety, and what it felt like to spontaneously understand that he would lay down his life for these kids if it came to that.

The sophomore boy, our guy, jumps in with a question.

“What do you mean, ‘lay down your life?’”

The teacher looks him in the eyes.

“I mean ‘lay down my life.’”

“What, like, take a bullet for us?”

“Yes.”

He strikes the word like a bell.

“You mean in real-life, or just as a teacher?”

The teacher’s gaze focuses on the boy, intensifies.

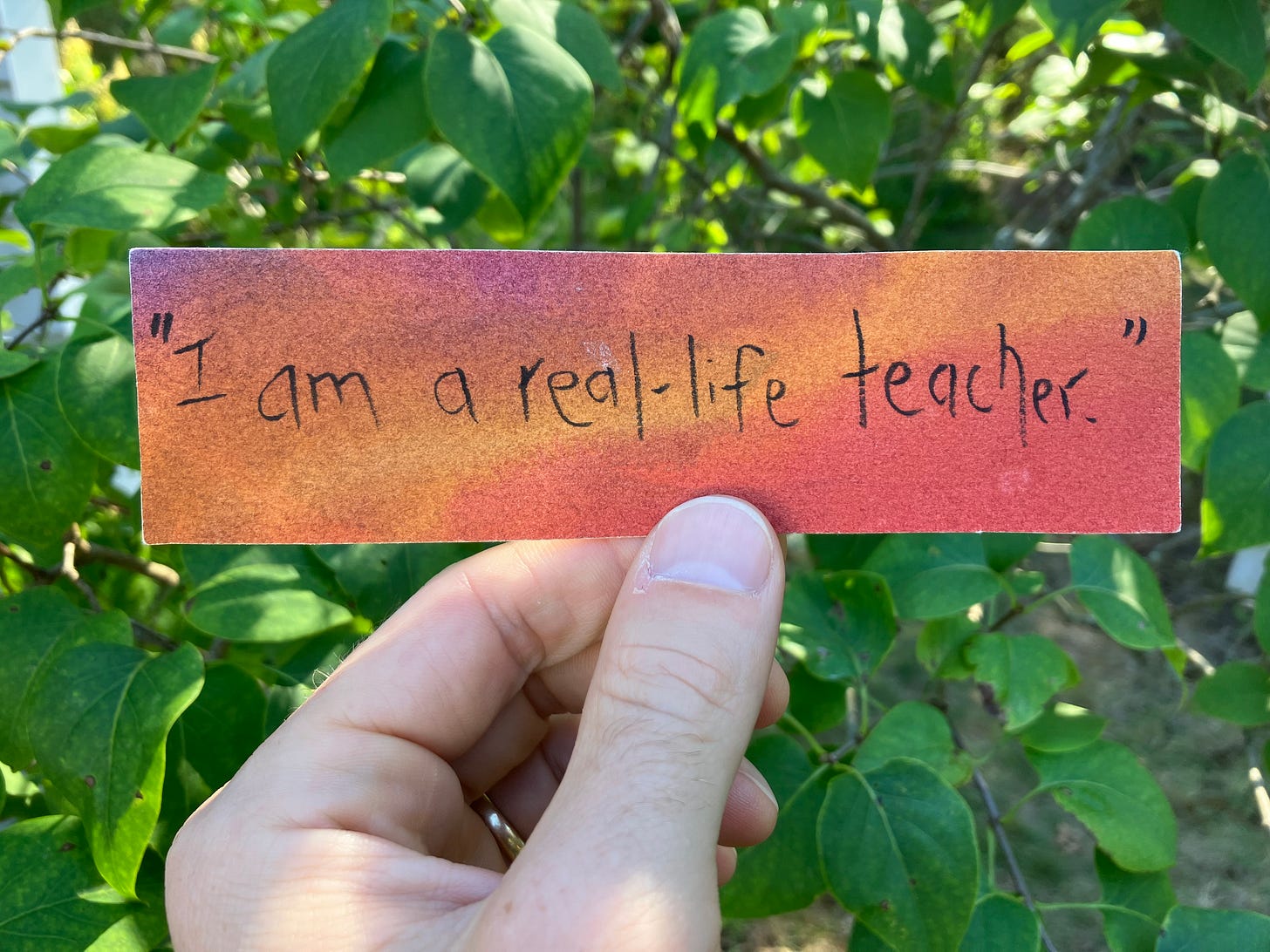

“I mean: I am a real-life teacher.”

His words reverberate throughout the circle. I feel it in my own body as a physical shivering up my spine, into my chest, the back of my shoulders. And in the stunned silence of the room, I sense the kids feeling it, too, feeling him, what he is saying and also what he is saying without saying.

What is something you love and cherish?

We’re getting closer, every circle, to the day when we can respond to this question without fear, without hesitation, in perfect beauty and perfect power: “You.”

This was so beautiful, it gave me chills. Holding all American teachers and children in a heavy heart from Canada. How strange and vulnerable it must feel for you, with a little baby now, to be there with your students, to see the babies they were in their faces.

Stunning. Thank you.